The ATHLOS team

Do people in the healthiest countries live the longest? And do people living the longest enjoy healthy older years? The reply to both questions is “no” and the phenomenon is known as the “health longevity paradox”: countries with the highest life expectancy have relatively low health scores, with a low healthy life year expectancy. In this month’s Special Briefing, we elaborate on the new definition of “old age” provided by the ATHLOS research project and how the social and political factors that influence ageing can inform our future policies.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), this diversity in older age is not random. The way older people age is influenced by genetic inheritance, but also by the environments in which they live. In other words, an older person could remain physically active not only because his/her physical condition allows him/her to move, but also if public transportation is within reach, or if the sidewalk leading to the park is flat enough. Designing adequate policy responses to our ageing populations is crucial to ensure health equity and active ageing.

Later life is about the years that remain

To guide policymakers in their task, ATHLOS meant to create a single metric of health, to understand the trajectories of healthy ageing for ultimately suggesting timely public health interventions that will optimize healthy ageing. During a public event, organized by AGE Platform Europe and hosted by MEP Milan Brglez at the European Parliament on January 28th 2020, the ATHLOS partners shared a set of guidelines on how to decrease health inequality and enable individuals to age in a healthy way.

Beyond the metric to inform policy making, the challenge of ensuring public health in ageing societies led to a debate on a new definition of “old age”.

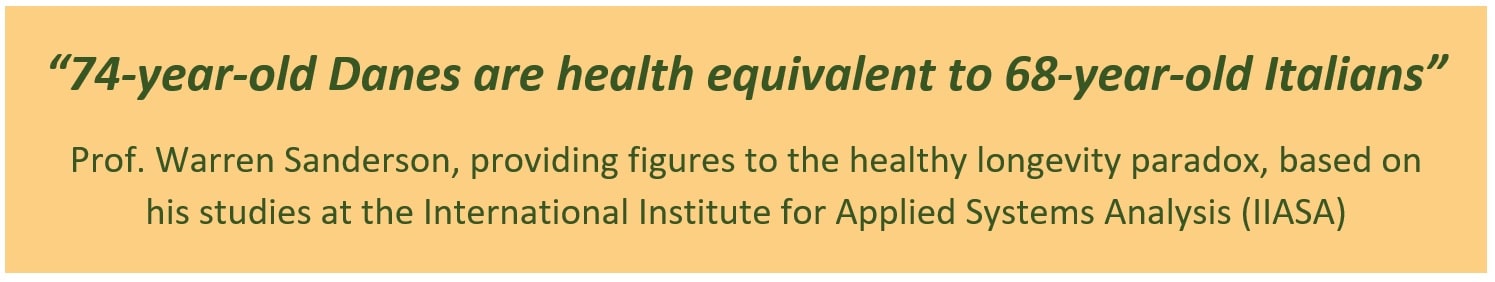

Thanks to the work performed by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, ATHLOS partners suggest to characterized people as “old” based on their remaining life expectancy of 15 years or less, rather than using a chronological basis. Following this definition, policy making would no longer user a same chronological age (e.g. 60 or 65 years old) for a whole population and could design fairer and tailored-made policies. For instance: opting out from the use of the chronological age to set up retirement ages would allow more equitable pension ages that duly consider life expectancy.

Stay healthy, a life-long learning process

The ATHLOS’ definition of “old age” goes hand in hand with the work on health inequalities, where old age reflects accumulated disadvantage such as geographic location, gender, ageist attitudes and practices. Genetics play a minor part in determining how we age, whereas our environment and our education are the main drivers. The life experiences accumulated from the earliest age have consequences in the way people’s health will evolve over time.

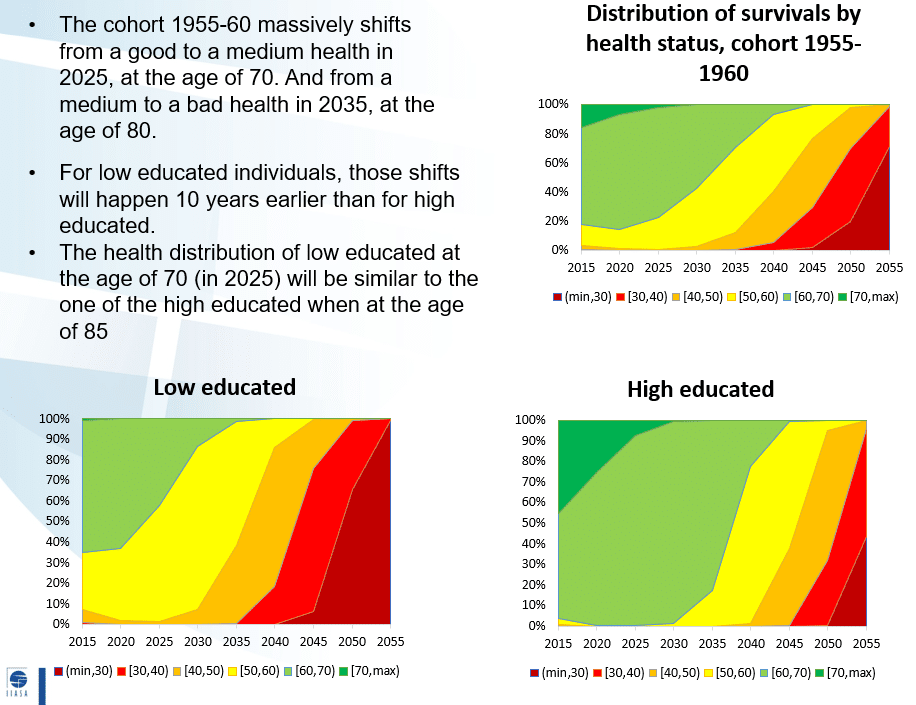

Through a micro-simulation tool set up by ATHLOS, evidence shows that increasing years in education at population level will positively impact on the population’s trajectory on health. Across countries, people with a greater level of education reported living healthier lives, with a significant gap with respect to people with lower educational level. Microsimulation studies indicated that among the six risk factors (arterial hypertension, obesity, smoking, depression, low physical activity and low education), improving education had the largest impact on future prevalence of poor health.

Our capacity to live long and healthy are the results of political and social factors. Appropriate policies (including interventions at an early age) can reverse the embodiment of socioeconomic disadvantage. Sustaining good health and wellbeing in older age thus depends on how effective our policies are in increasing the overall level of education and addressing health inequalities.

Education to challenge ageism is key!

In 2020, the World Health Organisation plans to launch its Decade for Healthy Ageing, an opportunity to bring together governments, civil society, international agencies, professionals, academia, the media, and the private sector for ten years of concerted, catalytic and collaborative action to improve the lives of older people, their families, and the communities in which they live. In preparation of this Decade, the WHO has been running a campaign to inform about ageism and its harmful effects on older persons’ physical and mental health. The task ahead of us goes beyond understanding health from a physiological perspective.

Not social inequalities alone impact people’s health: ageist languages, attitudes and mindsets play a big role too. For too long old age has been associated to ideas of incapacity, dependency, and passivity, thus defining in these terms who is old. Stereotypes and prejudice on old age affects our self-esteem, mental health and physical wellbeing in the long run.

“Age discrimination is harmful for health” research says.

It is more than time to change our mindset, our own health is at stake! Once again, investing in education is the most effective solution.

For more information on ATHLOS project and outcome, you may contact Ilenia Gheno and Nhu Tram.